National

Bitcoin “Whether you’re Binance or Ethereum, Dogecoin or Bitcoin, this is a great bill.”

By Eric Lipton and David Yaffe-Bellany, New York Times Service

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. — The debate took less than four minutes.

In the Florida House last month, legislators swiftly gave final approval to a bill that makes it easier to buy and sell cryptocurrency, eliminating a threat from a law intended to curb money laundering. One of the few pauses in the action came when two House members stood up to thank crypto industry “stakeholders” for teaming with state officials to write a draft of the bill.

“Whether you’re Binance or Ethereum, Dogecoin or Bitcoin, this is a great bill,” said Rep. John Snyder, R-Palm City, referring to crypto exchanges and coins.

Shortly afterward, the House voted unanimously to pass the measure. The Senate followed, sending the bill to Gov. Ron DeSantis for his signature after 75 seconds of deliberations.

Florida’s warm embrace of the cryptocurrency agenda is just the tip of an aggressive industry-led push to position states as crypto-friendly beachheads. Across the nation, crypto executives and lobbyists are helping to draft bills to benefit the fast-growing industry, then pushing lawmakers to adopt these made-to-order laws, before moving rapidly to profit from the legislative victories.

The effort is part of an emerging national strategy by the crypto industry, in the absence of comprehensive federal regulatory demands, to work state by state to engineer a more friendly legal system. Lobbyists are aiming to clear the way for the continued explosive growth of cryptocurrency companies, which are trying to revolutionize banking, e-commerce and even art and music.

Many states are racing to satisfy the wish lists from crypto companies and their lobbyists, betting that the industry can generate new jobs. But some consumer advocates worry that this aim-to-please effort could leave investors and businesses more vulnerable to the scams and risky practices that have plagued crypto’s early growth.

In Florida, the new money-transmission legislation emerged from a monthslong collaboration between Rep. Vance Aloupis Jr., R-South Miami, and Samuel Armes, who is starting a cryptocurrency investment firm, Tortuga Venture Fund.

“Vance has been an incredible asset to the blockchain and crypto community,” Armes said.

Similar teamwork has been on display in Wyoming, North Carolina, Illinois, Mississippi, Kentucky and other states, according to a New York Times review of state legislative proposals and interviews with legislators and their industry allies.

At least 153 pieces of cryptocurrency-related legislation were pending this year in 40 states and Puerto Rico, according to an analysis by the National Conference of State Legislatures. While it was unclear how many were influenced by the crypto industry, some bills have used industry-proposed language almost word for word. One bill pending in Illinois lifted entire sentences from a draft provided by a lobbyist.

In New York, at least a dozen industry players have hired lobbyists over the past year — including Blockchain.com, a crypto exchange, and Paxos, which is trying to set up a national crypto bank — collectively spending more than $140,000 a month, state records show.

The state proposals include bills to exempt cryptocurrency from securities laws intended to protect investors from fraud. Other legislation, such as in Florida, would exclude certain cryptocurrency transactions from money-transmission laws enacted to curb money laundering. Some would take even more radical steps, as in Arizona, where one legislator wants to declare Bitcoin legal tender so it can be accepted to pay off debts.

“Legislators want to be on the cutting edge, on the side of something new,” said Kristin Smith, executive director of the Blockchain Association, a Washington group that represents the industry. “We want to cultivate more champions.”

The moves have alarmed current and former financial regulators like Lee Reiners, a onetime supervisor at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, who is now at Duke University law school. He raised objections last year before North Carolina passed a bill exempting certain experimental cryptocurrency startups from the state’s consumer protection laws.

“States are being convinced you have to do this if you want to be competitive, so they’re rolling out the red carpet for crypto firms,” he said. “There’s no one pushing back saying there are big risks here to your citizens, of money laundering, consumer fraud and tax evasion.”

State legislators, many of whom have limited background in financial regulation, said they had little choice but to rely on industry experts, given the complexity of the crypto marketplace.

About two years ago, Jason Saine, a state representative in North Carolina, spoke with Dan Spuller, who wanted to pitch him on crypto projects and later joined the Blockchain Association.

“What would it look like?” Saine said he recalled asking. “You tell me.”

Their collaboration resulted in a bill that Saine introduced last year creating a regulatory “sandbox” for financial technology projects — essentially a special license allowing the industry to test new products without following certain regulatory requirements. The bill passed in October.

Solving the ‘Espinoza Problem’

In Florida, it began with the 2019 book “Bitcoin Billionaires.”

State legislators started working with the crypto industry after Aloupis read the book, which details the efforts of the Winklevoss brothers, who helped create Facebook, to generate new wealth in the crypto industry.

Aloupis said he had then spoken with the Gemini Trust Co., the cryptocurrency exchange that the Winklevosses founded, and Anchorage Digital, the first federally chartered cryptocurrency bank, for input on possible legislation he could introduce.

At the time, crypto executives were frustrated with a 2019 Florida court ruling that upheld the conviction of Mitchell Espinoza, who had sold Bitcoin to a Miami Beach police officer working undercover as the operator of a Russian stolen-credit-card enterprise. Espinoza was charged with laundering money and failing to hold a Florida money-transmission license.

The ruling meant that any two-party transaction involving cryptocurrency in Florida — even perhaps withdrawing money from a crypto ATM or buying crypto on an exchange — required sellers to have a state money-transmission license. For crypto companies, that necessitated meeting financial stability requirements and completing complicated paperwork. They called it the “Espinoza Problem.”

In July, the state ordered a dozen ATM providers that sell crypto in exchange for cash — including Cash Cloud, Coin Now and DigiCash — to register as money transmitters, despite appeals from the companies, documents obtained by The New York Times show.

Last year, Aloupis introduced the bill to exempt two-party crypto transactions, after lobbying appeals by Armes and a trade group he leads, the Florida Blockchain Business Association. (Its members include Binance, the large crypto exchange.) The bill failed to win Senate approval, and it was reintroduced for this year’s session.

Russell Weigel, the Florida commissioner of the Office of Financial Regulation, said he endorsed the legislation that Armes had championed.

“If I go and buy groceries at your food store, that’s a two-party transaction,” Weigel said. “Do I need a license for that? It seems absurd.”

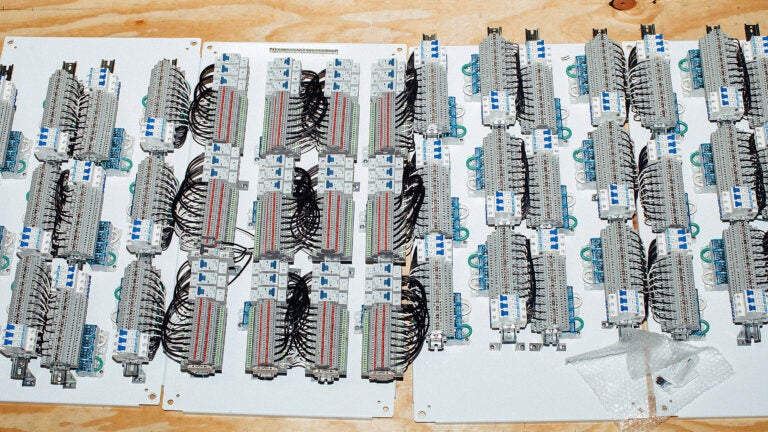

Lobbyists for Blockchain.com, a cryptocurrency exchange that moved last year from New York to Miami, and Bit5ive, which manufactures crypto mining equipment in the Florida area, joined the effort, contacting dozens of state lawmakers.

“They are very pro crypto,” Robert Collazo, the Bit5ive CEO, said of Florida lawmakers.

In the future, the company plans to raise money for crypto-friendly legislators in Florida, said Michael Kesti, Bit5ive’s lobbyist. The legislative affairs director of the Florida blockchain association, Jason Holloway, is already running for the state House, with donations — some in cryptocurrency — from Armes and others.

“I don’t want it to seem like we are paying for the influence,” Kesti said. “But we do want to support them.”

Bitcoin A Nationwide Lobbying Push

What has happened in Florida is playing out in other states as the crypto industry mobilizes to move its agenda — or defend against efforts to rein it in.

In New York, for example, concern about the environmental impact of crypto mining — in which large amounts of electricity are used to run computers that allow investors to get newly issued crypto tokens — has led to pending legislation to ban these centers. Another bill proposes cracking down on common forms of crypto fraud. The result has been a flood of lobbying in New York to combat these measures.

The opposite is happening in Georgia and Illinois, where legislators have proposed tax incentives for mining companies.

The Illinois bill emerged after Sangha Systems, a crypto mining company, converted an old steel mill in the state into a mining center and sought a special tax break to help finance the project.

Last year, a Sangha lobbyist took an official from the state Chamber of Commerce to visit the project in Hennepin, Illinois. Keith Staats, the chamber official, suggested modifying a state law to extend tax incentives to mining companies that set up shop in Illinois. He wrote a draft of the bill, which the chamber shared with Sangha.

“I looked at it, I iterated with them,” said Spencer Marr, Sangha’s president. “They made sure I was good with it.”

In January, Sue Rezin, a Republican state senator, introduced the bill — at the urging of the chamber, she said. She said she was not a crypto expert and had not “heard too much” about mining’s environmental impact.

The bill’s final version, which is awaiting action, is nearly identical to the draft written by Staats — including technical language about data centers and mining.

Not all legislative proposals have come to fruition. In Mississippi, Josh Harkins, a Republican state senator, proposed several crypto bills this year, including one exempting digital tokens from securities laws. He said he had gotten the idea from a lobbyist, Daniel Harrison, who was hoping to start a local blockchain trade association.

The bills died in committee in February. Harkins said he planned to revive them this summer.

Bitcoin Profiting on State Legislation

In some states where crypto legislation has passed, the architects of the proposals have moved swiftly to profit on the laws.

Last year, Kentucky passed a pair of bills creating tax incentives for crypto mining companies. One was sponsored by Brandon Smith, a Republican who leads the state Senate’s Natural Resources and Energy Committee.

A few months after the bill passed, Smith teamed up with Bitmain, a supplier of hardware for crypto mining, to propose a Kentucky-based repair center for mining equipment, a project he has since abandoned. Smith, in an interview, said he did not consider his work in the industry a conflict, given that he had not applied for the tax credits his law created.

Nowhere has the potential for crypto advocates to profit on new legislation become more apparent than in Wyoming.

Since 2018, Wyoming has established more than 20 laws that make it easier for the crypto industry to operate. A key player was Caitlin Long, a Wall Street veteran and a crypto booster, who helped engineer a 2019 law that paved the way for banks handling digital assets to receive Wyoming charters.

Not long after the crypto banking legislation passed, Long opened Avanti Bank and thanked Wyoming’s Legislature for making the business possible. The bank promptly received a state charter.

Last year, the business, now known as Custodia, raised $37 million from venture investors. “Somebody has to be in the arena, doing the work,” Long said.

Long worked on the banking legislation with Trace Mayer, a crypto investor and entrepreneur. Both had invested in Kraken, a crypto exchange that also received a state charter.

Critics have accused Long of using her influence to enrich herself.

“They came in and started writing legislation that really gamed it to their advantage,” said Robert Jennings, who served with Long on a coalition of crypto supporters in Wyoming. “It quit being about ‘How do we help Wyoming people?’ and quickly became ‘How do we game this system for the big crypto players?’ ”

Long said she had not decided to start a crypto bank until months after Wyoming’s legislation passed, when it was unclear whether others would take advantage of the law.

“It’s not easy to find the right people,” she said. “The crypto kids in hoodies, so to speak, were not likely to pass muster.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

Boston.com Today

Get news delivered to your inbox each morning.